Everything about my Park journey seems hinged upon my engagement with the arts, particularly music.

I remember very vividly, about two years into Middle School, begrudgingly churning out lacrimose melodies of Beethoven’s Pathetique sonata during assembly. The seven-minute piece was at best, an elegant lament, and at worst, a habit that, despite my great efforts, always teetered on the precipice of my memory. Stage-fright reigned in my mind that day, and I was sure everyone could tell. Then the final chord rang out, my eyes, delirious from REM-like movements, fixed on the dewy residue of sweat on the keys – a testament to how laborious this felt to 12-year-old me. I was done.

The immediate aftermath was anticlimactic. Here was a piece I had practiced to death, that had become somewhat of a chore, performed at the behest of I can’t remember who (probably my mom), that no longer enamored me. The melodrama of its entrance, the glitzy chromatic descents and ascents, all hogwash. I was, at that moment, ignorant of the importance of musical performance – the beauty that was and still is, sharing something of yourself, that you’ve worked to refine and to perfect. As I leapt up those carpeted stairs to freedom, a chic administrator stopped me before my summit. She was one I had seen gracefully whisking through hallways, and sauntering down corridors. I was curious about her; her kindness, which seemed to emanate from a distance, was intensely palpable now that we stood just feet apart. “I just wanted to say, my father used to play that piece almost every night when I was a little girl. It is very special to me, thank you for playing it,” she said. I was stunned, not because she spoke to me, which felt somewhat mythical, but because she was moved by my performance.

That moment revealed something that I haven’t forgotten since, something that repeatedly projected across my mind throughout my time at Park: performance is a practice in truthtelling. What I mean by that is musical performance, especially, is ironically one of the most honest things you can do. The very act of telling a story that is yours, or that of a composer or writer, demands vulnerability and humanity. Performance is an unceasing lesson in authenticity; who are you, really? And are you prepared to tell the world?

Park prepared me — and encouraged me — to tell the world, on every mountaintop, in the deepest, shadowiest corners, who I was.

Pretty much every month in high school, I begged my friends to accompany me during Goldsoundz. I played, they played, we all played, often unprepared to show anyone, anything. But we did it anyway because we were empowered by giants like Adele, Maeve — and, most importantly, each other. Goldsoundz gave us the space and the latitude to confess, to proclaim(!), to profess our undying love for our crushes, to brood over betrayals, and to develop our skills as performers. We could sing with our friends, conspire against our enemies all within the familiar confines of the black box.

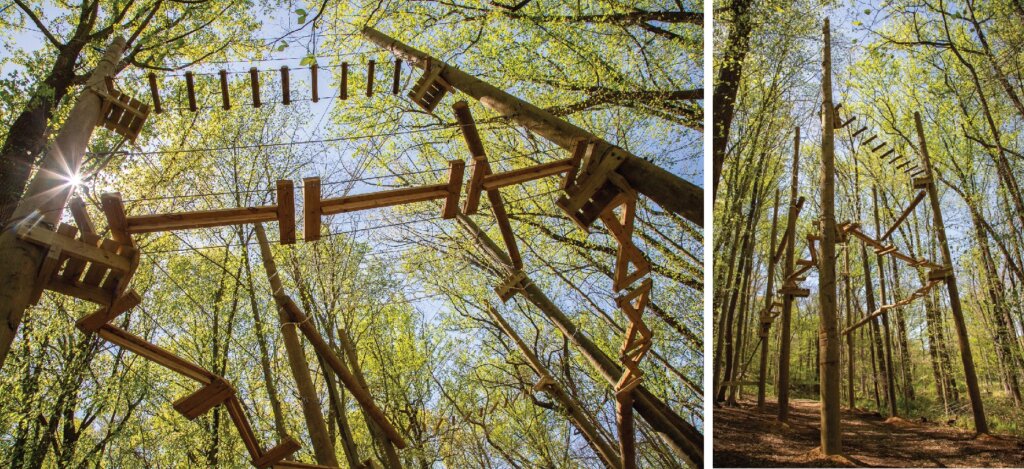

It is (very annoyingly) a classic story. I wish I could say something more interesting like, “I came upon a group of Appalachian folk singers on the challenge course and that changed my life.” But alas, mine is quite cliché. I was mentored and nurtured by devoted teachers who I could tell ate, drank, and breathed music, and surrounded by equally ravenous peers. I had the privilege, which should really be a universal norm, to have an education that thoroughly integrated my musical interests. I tried so many things: auditioned for and performed in theatrical productions, joined Eightnotes and Parksingers, had a brief tenure with the Jazz Collective, and toiled in painful silence in Adele’s Music Theory course. It was essential, so joyful, and I look back and wish I could do it again, and again, and again.

What I carry with me now are fragments of a very delicate mosaic that lies somewhere, in my subconscious, perfectly preserved. I can sometimes access it when I go to that REM-like place while I sing or play. There are images, feelings, moments that reinforced my adoration for music, and my growing appreciation for telling people just who I really am. Since then, I’ve done a lot of performing; whether at the Kennedy Center, jazz clubs, or the gothic auditoriums at Yale, I’d like to move people. Through honesty, through performance.

Vyann is a rising singer/songwriter and composer devoted to creating music that speaks to her life and honors traditions of the Black diaspora. Her writing draws primarily from neo-soul, folk, jazz, and classical styles. Born and raised in Baltimore, she studied classical piano for 13 years, and is a self-taught jazz vocalist. She recently graduated from Yale University with honors in both Music and Public Health. Her influences include Nina Simone, Roberta Flack, Stevie Wonder, H.E.R., Erykah Badu, Adele, Miss Lauryn Hill, and many more. She has written and composed for several musical/theatrical productions at Yale and beyond. Her most recent commission was featured in opera star Leah Hawkin’s homecoming recital at Morgan State University. Currently, she has two singles available on streaming platforms, a rendition of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” and an original piece by composer Nasir Scott, entitled “Black is Beautiful.” She will be releasing more singles this fall, notably an original piece entitled “Mothering Blackness” based on the poem of the same name by Maya Angelou.

Find the full Fall 2025 issue of Cross Currents here.

Back to The Latest