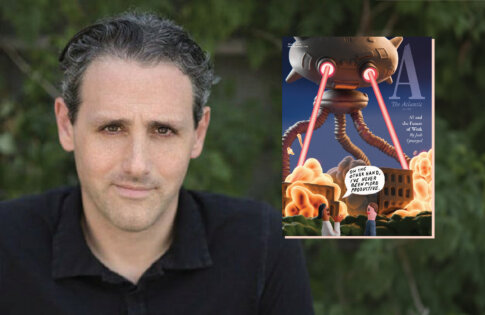

The Ravens’ Daniel Stern ’12 in conversation with Susan G. Weintraub, his former Postscript Advisor

Our Fall 2024 edition of Cross Currents magazine celebrates the work we do at Park supporting young people in becoming confident questioners and responsible citizens of the world. Teachers from each division offer glimpses of how our students develop the skills and confidence in asking questions and experience the joys and confidence in open inquiry. We also share stories from alumni, like Daniel, reflecting on how their time at Park inspired or influenced their professional paths and experiences.

Daniel’s story from playing football at recess in Park’s Lower School, to Yale University, to a career in the NFL, is featured below.

Daniel Stern ’12 loves football. Always has. Daniel had career options galore. He was a Mock Trial leader at Park and Yale University, editor-in-chief of The Postscript, and a sports writer at Yale. Becoming a lawyer or writer would have been easy, expected. Instead, he pursued football, specifically coaching.

Daniel is living a dream — and it’s a busy one. His nine years in the NFL began in 2016, right out of Yale, where he earned a degree in cognitive science. Now, as director of football strategy and assistant quarterbacks coach for the Baltimore Ravens in the middle of a winning season, Daniel is at work six days a week by 6:30 a.m. (plus games on Sunday) and continues far into the night, sometimes sleeping at the Owings Mills practice facility rather than going home.

Given this break-neck schedule, it was hard squeezing in time to talk. If you know Daniel and how much he loves football, you might appreciate that he packed a mountain of information into a couple of hours of conversation late one Friday night. There were not many questions, but lots of answers.

Here, then, is Daniel’s account of his journey from Park into the headset of Head Coach John Harbaugh and the Ravens staff.

Why did you major in cognitive science at Yale?

I didn’t go through high school and college feeling I was on any professional track. Park taught me to appreciate learning for its own sake, and to follow your interests. So when I got to college, I took classes I thought I would like. From the start, I was interested in speaking, writing, history, strategy, and psychology — especially decision making and behavior. Cognitive science was an interdisciplinary major that let me take classes in a bunch of different areas. We had to choose a track or unifying theme, so I called mine “Decision-Making, Strategy, and Persuasion,” which I thought could end up applying to any field I’d go into. The credits came from all over: Behavioral Econ classes in the School of Management, game theory and data analysis classes in Econ/Comp Sci; behavioral and neuroscience classes in the Psych department; even a class in the Law School.

Football?

I fell in love with football in fourth grade at Park playing two-hand touch at recess; watching the NFL all day on Sundays; staying up until midnight playing Madden against my friends. There was so much strategy involved and the whole team mattered. I begged my parents to let me play Towson Rec tackle (the Towson Triumph Football Program), and they finally let me do it in Middle School.

When you’re little, you dream of being a player in your favorite sport, but I realized faster than some of my friends that wasn’t going to happen, so I started to think about what it’d be like to coach. I had no idea how to make it happen and wouldn’t have said it was possible, but I think the best thing I did was simply always try to stay involved.

During my summers in high school, I coached 7 v. 7 football at my summer camp. The Towson Rec program ended at high school, but my younger brother Zach (Class of 2019) started playing in Lower School, so as I got older, I became an assistant coach for his team. Helping coach Zach’s team became a fall sport for me when I was in Upper School at Park. During spring of my freshman year at Yale, I started managing Yale’s team: I filmed practices, set up equipment, and caught balls from the punters and quarterbacks. Over time, I started traveling and doing more, like getting into the coaching film breakdown: charting situations, formations, and personnel groups on the field.

I wasn’t doing those things because I knew it’d take me somewhere — more just to stay part of a team and around my favorite sport. But I also knew that if I didn’t do these things, I would have no chance of being in football later on. There are so many people trying to get football staff roles, but the number one way is to play at a high level. I didn’t have that, so I needed whatever other experience I could find.

The summer before my junior year, one of our athletic directors advised me to develop a data analytics skill set to supplement the student assistant experience. Analytics was a hot hiring area in sports, and something most teams would want from my résumé as a non-player. I beefed up on classes in data programming and computer science, and added an independent study where my advisor and I read all the empirical research we could find published on football strategy, and did a couple of our own projects. People were starting to look at more and more tactical stuff with data: modeling value of different picks in the NFL draft, fourth down decisions.

At that point, I was starting to feel like I had enough different experiences and angles to see if I could find some type of entry job in football.

Getting there

Fall of my senior year, I emailed a staff member at every team I could guess an email address for, college and professional. It turned out that because I’d added the data programming experience, I got a stronger response from the NFL than college football, mostly on the player personnel side. I was close to finalizing a post-grad summer internship with another NFL team’s front office. It wasn’t a coaching path, but I was juiced either way to learn and see where it went. But before it was final, I got an email from Baltimore. They were looking for an analytics assistant to help the coaching staff — accessing and studying data about opponents, schemes, and game strategy. Whether it had been Baltimore or not, it was a great fit because I was passionate about continuing to learn that side of the game. It was an opportunity to work for and learn directly from coaches. It was also a great organization, let alone my hometown team. I ended up getting an offer, and I was lucky they took the chance. They helped me grow so much, so fast. I asked coaches what they needed to do their jobs, tried to learn what they were working on and help make it better or easier, and took on as many of my own projects as I could to study strategy, watch film, and contribute ideas. I always assumed that to move from data to coaching, I’d have to learn enough on my own there, then get a graduate assistant coaching job with a college team. But they allowed me to learn and pivot all within the Ravens organization.

Nine years in the NFL

Coach Harbaugh tells us all: “The more you can do, the more you can do.” As in: the more things you learn to do well, the more we’ll let you help in different areas. I feel like I’ve lived that over the past few years. From helping build strategies and programs to use all the football data we have, to projects that start and end with the film, to gameday strategy, to scouting reports and teaching materials, I’ve had a platform here to study and present lots of topics to audiences of coaches and players. I am involved both in creating new tools and templates for multiple seasons/long-term, as well as in the weekly coaching support work to prep for the next game: playbook drawings, ideas, “practice scripts,” player study materials.

After four years working as a resource for the whole staff, I was formally put on our offensive staff from 2020-22 (one year each with tight ends, running backs, and wide receivers) before moving to the defensive staff last year, working mainly for the coordinator and in the inside linebackers room. This year, I’m back on offense and in the quarterbacks room.

The basic weekly assignment is: watch and analyze as much as you can in assigned areas. Try to find: any edges or areas to exploit, best practices and processes for game decisions, solutions to problems we’ve had or that other teams present, and ideas and information for the game that can help players and other coaches succeed.

How do you apply the Park School philosophy to your job with the Ravens?

To me, the Park philosophy is all about having the audacity to challenge, curiosity and open-mindedness to learn, trust to believe, and positive expectations to speak to life. I still believe in all of those.

Park taught me to chase my interests confidently down unclear roads — with an open mind — and to follow wherever they led. No idea where I’d be without that approach.

I think success in the NFL (or any competitive industry) comes from finding new edges and advantages that can set you apart from competitors (teaching, strategy, gameplanning, etc.). Finding any of these requires not only confidence to bring up a new solution or idea, but also the curiosity to look for it, and the humility to debate and consider its flaws sincerely.

And Park is all about starting with positive expectations of others. I firmly believe that applies to coaching and team sports. Positive expectations are visualized, internalized, and repaid with results.

Park fielded a football team 100 years ago from 1920-26, ending with a record of 8-20-2. Is it time to try again?

No, but they should have Flag Football. I actually bet a lot of kids would play. Would be fun to coach.

Find the full Fall 2024 issue of Cross Currents here. Read more about Daniel in our Alumni Stories here.

Back to The Latest